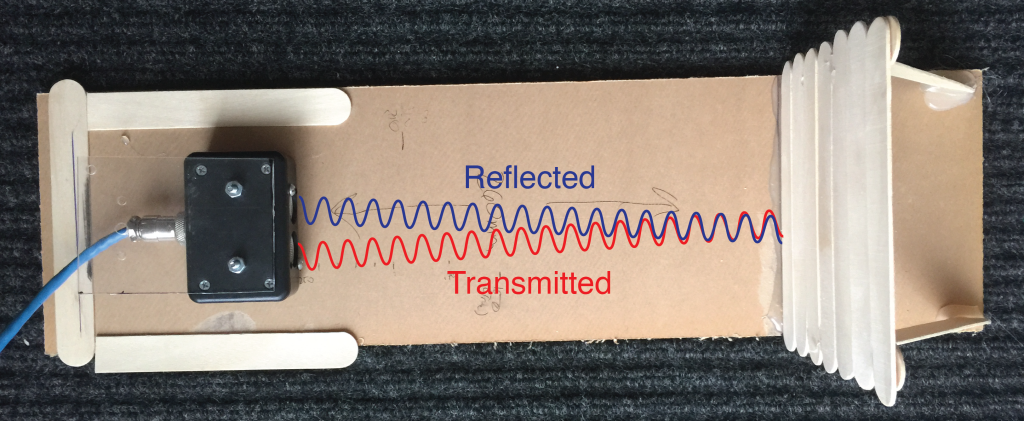

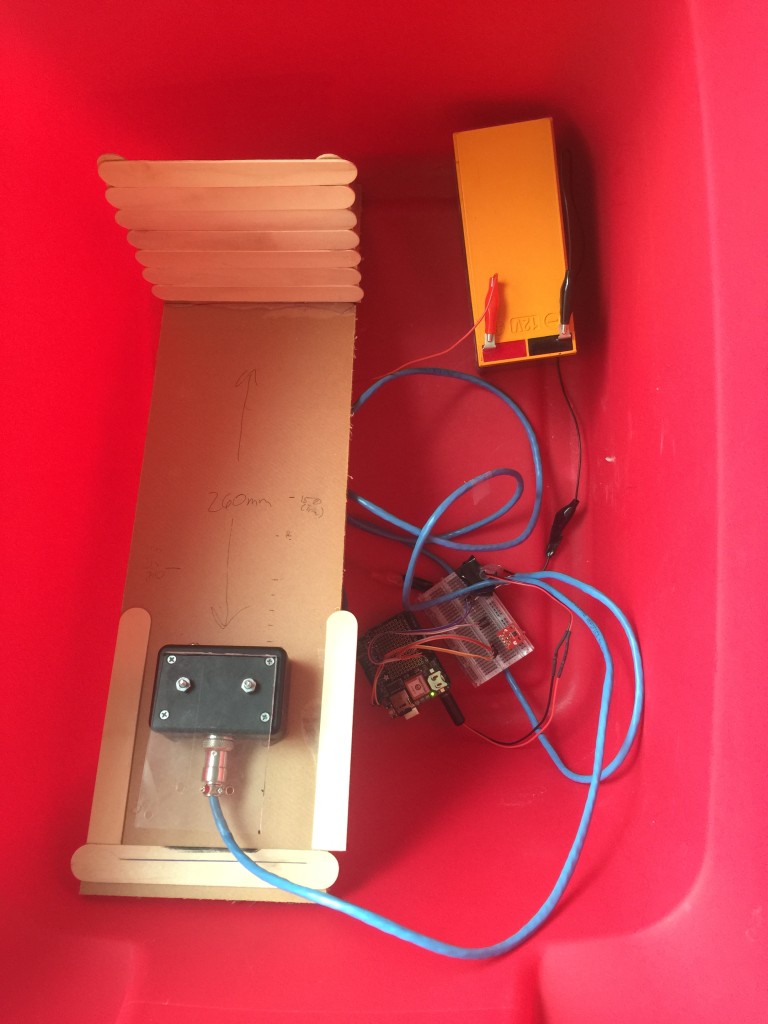

Ok, I've been sitting on this topic for awhile, but I was recently inspired to revive this post after being asked some very general questions by a tour group that came through the lab. Next time we'll be back to doing some data collection and analysis. Maybe gravity tide measurements? Anyhow, on with the topic of the day: knowing the fundamentals.

On a (now old) episode of the podcast Technical Difficulties, Gabe Weatherhead (@macdrifter) was chatting with Brett Terpstra (@ttscoff) and Rob Trew (@complexpoint). The show was mostly about how everyone got started writing computer code and some tool suggestions. One line made me stop on my walk home to type it into my reminders to write this post.

Rob quoted a line from the Windows 95 API Manual (a programming interface manual for the non-programmers out there). It said "The nature of an expert is not someone who knows all the details, it's someone who understands the fundamentals really well." Rob points out that therein lies the key to problem solving. This statement really resonated with me when I looked back on problems that I've encountered in the past, both scientific and technological.

We often think of an expert as someone that is in the top few percent of the knowledge leaders in their field. Experts should know all of the details of their subject, including the latest "bleeding edge" research right? While many experts do stay up to date, I began re-examining the people that I considered to be experts.

The professor may be the ideal example of this. While academics often get the connotation of the aloof and socially insulated genius, it's really not true. (In fact, our academic heroes are just people too, listen to the latest Nerds on Draft for that side story.) Professors have to teach the same material over and over again during their career. Sure, they should be pushing the frontiers of their field within their research group, but that's not what should be done in the education potion of the career. When you teach something, you end up deeply learning it yourself. In fact, that is part of the value in teaching! Be continually re-iterating the fundamentals to ourselves, we can stay primed to approach a new problem with a honed set of tools.

What could these fundamentals be? Well, that depends on your work. Maybe it is knowing the basics of programming or how to do basic chemical balance/thermodynamics calculations. Maybe it is knowing the fundamental operation of the product that you sell, or knowing the backstory to a concept you are helping someone with (such as the history of a topic).

I can't count the number of times that I've been trying to figure out a solution to a problem or how to build something when, after hours of no progress, something will make me start again. This time I look from a fundamentals viewpoint and can generally see a way to a solution or at least enough of the way to be able to ask an intelligent question.

Ideally, we are prepared for this way of problem solving by getting the basics of many fields during our undergraduate careers. Unfortunately that doesn't always happen. We have all sat in a math class, economics class, etc when the professor goes deep into a subject that they adore and leaves us in the dust. Another common occurrence is that the application of the fundamentals is not shown or sometimes not even implied. Not that students should be guided by the hand to the solution, but sometimes a firm nudge is necessary. I didn't necessarily appreciate this early in my undergraduate career, but later became a mass consumer of basic knowledge.

Next time you are on Amazon or in the library, browse over to a section with a topic of interest and pick up an introductory book. Read some sections, try some problems, and you'll be amazed at the other angles you can suddenly see as avenues of attack to a problem. You can even pickup some of your old text books and remind yourself of the fundamentals that all too often slip from our minds with time.